- Home

- James T. Andrews

Into the Cosmos Page 38

Into the Cosmos Read online

Page 38

visit to Canada in 1961, for example, Titov was asked by the press to ad-

dress rumors that he had not written the account of his flight that had

appeared (attributed to him) in the Atlantic Advocate.51 The Chicago Daily Tribune asserted that Titov could not have orbited Earth fewer than seventeen times and still land in the targeted landing zone, perhaps suggesting

that his lack of “choice” in the matter made the feat less remarkable.52

In Leipzig a Western journalist reportedly asked whether pictures of the

Vostok 2 capsule released to the press were authentic. More profound were questions raised by an American journalist as to whether Titov had even

launched into space or left Earth at all.53

These components of Western reports of Titov’s flight established a

story that drew on familiar elements of the Western Cold War narrative

of the Soviet enemy. This story defined Gagarin and Titov as cogs in the

Soviet space machine—going to space, certainly, but having little to no

control over their mission or even their account of it—and performing

their parts behind a veil of relative silence and secrecy. Some reports even

set them against the free, individualistic, plucky American astronauts

Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom. A NASA bio of Shepard perpetuates this

narrative still, asserting: “Despite the fact that Gagarin’s flight had tak-

en place three weeks earlier, Shepard’s flight was still a history-making

event. Whereas Gagarin had only been a passenger in his vehicle, Shepa-

rd was able to maneuver the Freedom 7 spacecraft himself. While the So-

viet mission was veiled in secrecy, Shepard’s flight, return from space,

splashdown at sea and recovery by helicopter to a waiting aircraft carrier

were seen on live television by millions around the world.”54 Shepard’s

control over his machine defined the historic nature of his achievement,

which was a spectacle of freedom and openness because it was broadcast

on live television. In this way Western narratives fit Titov’s flight into

a longstanding vision of the motivations, goals, and methods of the Soviet

state.

Cold War Theaters 253

The socialist media built uncritical celebrity narratives heroizing

the efforts of Titov and the other cosmonauts. The media persistently

recounted the details of their personal lives, followed the growth of their

young families, and insisted on the unmatched, superbly executed na-

ture of the flights. The significant discomforts (and possible mistakes or

failures) of the launches found no place in this narrative. During Titov’s

flight, for example, he had complained of extreme physical reactions; not

only did such complaints not appear in the press, but reports asserted

that Titov had not experienced any markedly abnormal changes and had

remained “completely fit for work” throughout.55 There was, then, a cer-

tain disconnect between the man and the celebrity. But in the mediated

Cold War, who these men were in “real life” was not as important as

the social role their mediated personas performed in the GDR.56 In their

study of “socialist heroes” Yuri Gagarin and Adolf Hennecke (an East

German Stakhanovite), the historians Silke Satjukow and Rainer Gries

have shown how central such figures were to the social construction of

the nation. Hennecke, for example, appealed to other East Germans be-

cause of his common working-class background, just as Gagarin did. He

represented the everyday, but at the same time he represented something

extraordinary that could yet become part of the everyday. Worker-heroes

such as Hennecke “were supposed to be a role model (for the socialist

working people), for the socialist consumer they were supposed to be

a glimpse of the future (Vorschein) [ sic]. Because just as the hero Hennecke lived today, provided with a good apartment, outfitted with a car

and furnished with many privileges and status symbols, so should the

many live tomorrow.”57 These representations of Hennecke, Gagarin, and

Titov served to bind East Germans to a socialist future.58

On the day of his flight Titov became a star overnight in the GDR.

The nightly news devoted the August 6 evening broadcast almost exclu-

sively to reporting his flight. It disclosed the details of his personal life

and the statistics of his flight that would be reiterated often in the coming

weeks: the spacecraft weighed in at 4,731 kilograms, for example; each

Earth orbit took 88.5 minutes; at its widest orbit the capsule was 257 ki-

lometers from Earth. It sought to “nationalize” the story by including

East Germans’ recollections of, and reactions to, the event. The broadcast

included short reaction interviews with East Berliners taking in the beau-

tiful summer weather at the beach in southeastern Berlin. It reported

on youth who had gathered at a Pioneer camp to listen for Titov’s voice

254 Heather L. Gumbert

over the airwaves and then to write him a letter. It included a sound bite

of Titov speaking from space that had been recorded by an East German

postal worker and amateur radio enthusiast from Beelitz (southwest of

Berlin). The only other substantial reports of this broadcast included

a segment on Yuri Gagarin’s stay in Brazil and a final item reminding

viewers of an upcoming television address by Khrushchev advocating for

the conclusion of a peace treaty for Germany.59

The official narrative of Titov’s trip was celebratory and triumphant,

tempered by portentous reminders of the urgent geopolitical situation. In

the second week of August the television news reported on the progress

of registering border-crossers, the trial of four East Germans for espio-

nage, East German “orphans” of parents who had left the GDR and, of

course, Khrushchev’s demands for a peace treaty. For some people the

increasingly aggressive language of border crossing and espionage, along

with renewed demands for a peace treaty took on new, more ominous

meaning after the success of Titov’s mission. The Chicago Daily Tribune

published the testimony of a doctor who claimed to have fled Berlin with

his family through the still permeable checkpoint at the Brandenburg

Gate on August 13. Dr. Ernst Lehnhardt described his life in the GDR

as successful and relatively comfortable: “I lived in a good residential

area in East Berlin [in] . . . our own house. It was large with a pleasant

garden, but run down. . . . I had no serious complaints.” But by early

August, Lehnhardt had become wary of the possibility that authorities

would close the sector border and even build a wall: “Some believed even

then that a wall would be thrown up between the two parts of the city.

Ulbricht . . . said this never would be done, but we did not trust him.

. . . Others soothed themselves with the belief that a wall was impossible.

But I thought to myself, what is impossible for a system that sent Titov

. . . around the world 17 times?”60 For Lehnhardt, Titov’s triumph repre-

sented the growing strength of the socialist bloc and made the prospect

of a wall more likely.

The growing strength of the socialist bloc, along with the incre

as-

ingly aggressive language of border crossing, led some to conclude that it

was a good time to leave. Titov did not appear again in the nightly news

until August 26, when he led the news with his announcement at a press

conference in Moscow that he would be traveling to the GDR. After this

announcement, a narrative began to emerge that replaced the contracting

Cold War Theaters 255

space of the East German world with the expanding world of the socialist

community.

Titov’s Visit

In the GDR the media began crafting the legend of Titov even before

his arrival. In its August 20 edition—the first to appear after the bor-

der closure—the weekly radio and television magazine Unser Rundfunk

(Broadcasting) lauded Titov, his flight, and the Soviet Union. The story

described Titov’s “firm assuredness and steadfast calm, inspiring brav-

ery and boundless energy.” His spacecraft, though very complicated, had

been utterly reliable, even “flawless” in its operation. The article noted

that the craft had even landed at the predetermined coordinates, pointing

out that this mathematical feat surely represented a sign of Soviet superi-

ority. With this spaceflight “a new chapter in the scientific exploration of

space has been written, composed by the builders of socialism.”61

German Titov arrived in Berlin on the afternoon of September 1, cap-

turing the imagination of the East German media. East German televi-

sion covered his arrival in a special simultaneous broadcast for viewers

in the GDR, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Austria—one of the first of

its kind in East German television history.62 The mood at the top of the

broadcast was relaxed, as the moderator introduced the parade route for

Titov’s motorcade and introduced commentators from Czechoslovakia

and Hungary. The moderator then read a letter from Titov to the East

German people before a reporter on location set the scene at Schönefeld

airport in southeastern Berlin. Titov’s arrival at the airfield, at long last,

charged the atmosphere. The large crowd surged toward Titov and his

official host, Walter Ulbricht. The television camera, still relegated to the

back on the crowd in the early 1960s (and not positioned front and center

as we might expect in contemporary television coverage of such news

conferences), valiantly held its own as the excited throng jostled for the

best view of the hero.

After some brief remarks from Ulbricht, Titov took the microphone

and praised the GDR as “the great peasant and worker state,” which had

“accomplished a lot” and was a place where “socialism grows stronger ev-

ery day.” His crowd-pleasing conclusion spoken in German “Es lebe Frie-

den in der ganzen Welt” (Long live peace in the whole world) set the crowd

256 Heather L. Gumbert

on fire. Thereafter it took some time for the dignitaries to move through

the crowd to their motorcade. The print press presented an equally lau-

datory picture of Titov’s arrival. The Berliner Zeitung reported that “the whole of Berlin was on the streets. . . . Everywhere one looked there were

smiling faces . . . [and] cheerful songs.” At Schönefeld airport the tarmac

“teemed” with a crowd of ten thousand; Titov appeared, “beaming,” from

the door of the aircraft before deplaning with his “picture-perfect” wife,

Tamara. “Berlin,” screamed the headline, “has never experienced this.”63

The propaganda value of Titov’s accomplishment and subsequent

visit so soon after the crisis of the August 13 was laid bare repeatedly

in newspaper coverage of the event. The newspaper of the Free Ger-

man Youth organization reported “Our Successes Prove: We Are on the

Right Track.”64 The national daily newspaper Neues Deutschland asserted:

“Titov’s deed announces to all peoples: Socialism is the strongest power

in the world.”65 The newspaper of the Free German Trade Union Associa-

tion, Tribüne, declared: “The Roots of Our Success: The Socialist Planned Economy.”66 Neues Deutschland quoted Ulbricht’s words of welcome:

“Cosmonauts herald the great future of Communism.”67 Finally, the Ber-

liner Zeitung exclaimed: “He can land anywhere.”68

In the television coverage as well as the print press, the story of Titov

was the story of the superiority—even victory—of the socialist world

over the capitalist West. This was a victory both moral and scientific. In

a speech welcoming Titov to Berlin, Ulbricht exclaimed: “What a great

achievement and precision work of the Soviet scientists, engineers and

technicians! What a great success of the Soviet Union and her superior

social order! What a triumph of the young heroes of the great Soviet coun-

try, who are in the process of putting the forces of nature in the service of

man and paving the way into space as fearless pioneers of humanity!”69

The Vostok missions seemed to lay bare the superiority of Soviet sci-

ence, particularly when set against the accomplishments of the American

space program. NASA had launched two suborbital flights earlier that

year, leading the West German publication Der Spiegel to claim just days before Titov’s launch: “US 2 USSR 1,” referring to the number of manned

launches that had taken place. The GDR press took exception to the “gro-

tesque equation” of the Soviet and American flights, which clearly were

not the same in the scope and breadth of their missions. Unser Rundfunk

lampooned the Spiegel article as an example of the lies told by “bour-

geois statistics.”70 This was not the first time this had cropped up. The

Cold War Theaters 257

American space program had already been skewered in a cartoon repro-

duced in the GDR (after it first appeared in West Germany and the Soviet

Union) after Gagarin’s pathbreaking flight in April 1961. In the cartoon

an American spaceman sits atop an American skyscraper, scratching at

the clouds while above the clouds a Soviet spaceman rides his rocket into

“space” (here, the upper left-hand corner of the image). The skyscrapers

are adorned with well-known brands and slogans, including “Coca-Cola”

and “Mach Mal Pause” (Take a Break), implying that American failure

to reach outer space was the fault of capitalist market culture.71 During

Titov’s visit reporters drew a finer point on the issue, posing the ques-

tion of whether the flights could indeed be compared. At an international

press conference in Leipzig, Titov argued that in order to “count” as space

travel, the spacecraft had to orbit the earth at least once, which neither of

the American flights had done (figure 10.1).72

But media coverage of Titov went beyond simply acclaiming him as

a socialist hero East Germans could claim as one of their own. Instead,

it made close connections between Titov and his trip to space, and the

decision to cut off the border in Berlin. The broadcast of Titov’s arriv-

al in Berlin intercut live images from locations along the parade route

with filmed reports on related topics. One report, for example, followed

a group of children as they introduced model rockets the

y had built to

celebrate the arrival of Titov and concluded with an animated film of chil-

dren going into space. The most important of these filmed reports, in

terms of the gravity of reportage and the time devoted to its broadcast,

was a film on the subject of Berlin, capital city of the GDR. Ostensibly,

the film introduced Berlin to audiences of the affiliated television organi-

zations in Eastern Europe; its content, however, set out the official argu-

ment for the construction of the Berlin Wall. It depicted the geopolitical

problem of “two Berlins,” a problem that had been solved by the measures

of August 13 (the border closure). The film used the language of “people-

trafficking,” “espionage-central RIAS” (referring to the American radio

station in West Berlin Radio in the American Sector), and the decadent

West that was long familiar to East German viewers. Due to the measures

of August 13, it concluded, “peace is in good hands [in the GDR].”73 This

film was just one example of a trope that was repeated on television and

in the print press throughout Titov’s visit, narratively joining Titov’s ac-

complishment with the “accomplishment” of GDR authorities. Titov was

a soldier in the battle against the West. His trip to space was an important

258 Heather L. Gumbert

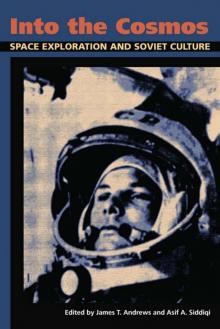

Figure 10.1. This cartoon is from the East German newspaper Volksstimme in 1961, in anticipation of Titov’s visit to Berlin. The caption reads: “The Americans couldn’t make up the lead. They are trying to scratch space; the Russians already control it.” Source: Volksstimme, May 5, 1961.

blow against the West, just as the border closure had been and would

continue to be an important challenge.74

Press reports of the visit allowed Ulbricht to bask in the reflected

glow of the cosmonaut. Titov was a hero who represented the best of the

socialist world; more important, he was impressed by and supportive of

the measures taken to close the border. Titov echoed language used by

the authorities since August 13, declaring: “It’s nice to see the develop-

Cold War Theaters 259

ment of the worker-peasant state. All Soviet people are very happy about

that and learn with satisfaction how successfully the measures for the

protection of the borders are operating. With that, the plans of the West

Into the Cosmos

Into the Cosmos